Family Structure

Family unit stability and its incarceration implications

Background

Decades of research has found that family structure has the power to impact a child’s development. For example, children growing up in two parent homes tend to have better health and social outcomes than those who grow up in single parent homes 1. Teen pregnancy (defined as pregnancy between the ages of 15 and 19 years old), costs U.S. taxpayers between $9 and $11 billion dollars per year and Virginia is estimated to spend $183 million dollars on factors related to teen pregnancy2.

Not only are teen mothers more likely to drop out of high school, find themselves unemployed, use public assistance, and have lower incomes, but their children are also at elevated risk for a variety of similar outcomes3. The fact that low levels of family supervision are related to higher rates of juvenile delinquency in adolescents is particularly troublesome in the context of incarceration trends4. The children of young, single parents, particularly those also experiencing financial strain, are thus at heightened risk of delinquent behavior, putting them at increased risk of encounters with law enforcement. Over time, these encounters may predispose these individuals to heightened risk of entering the criminal justice system. When these individuals are thus absent from family life themselves, the potential exists for the cycle to repeat itself, as children of incarcerated parents are more likely to be involved with the criminal justice system themselves5.

Main Findings

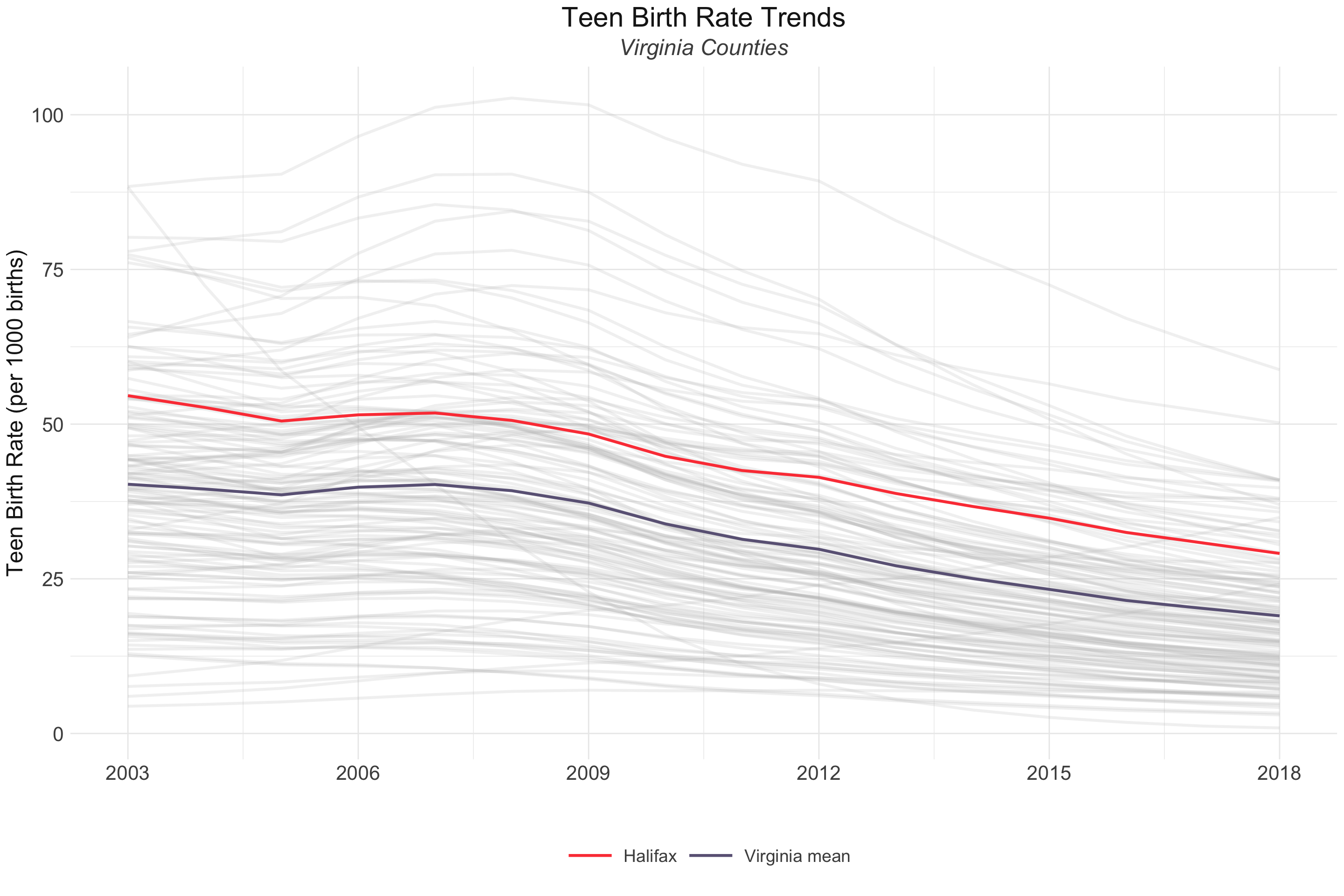

In 2017, the rate of teen pregnancy (per 1,000 women) was 18.8 in the United States. In the same time period, the rate of teen pregnancy (per 1,000 women) in Virginia was 15 and in Halifax county the rate was estimated at 30.86. This put Halifax at the 24th highest rate of teen births out of 134 counties in Virginia. While the number of teen births has been declining since 2003, the fact that Halifax was in the upper portion of the distribution indicates the potential for effective interventions on this factor.

The overall decline in teen birth rates across Virginia in the past decade is encouraging, but there exist distinct spatial clusters where higher teen birth rates exist. In 2018, south west and Southside Virginia both seemed to have higher teen birth rates than much of the rest of Virginia.

Given that these areas tend to be rural (a pattern consistent with current research)7, efforts to reduce teen birth rates that focus on this cultural context may be particularly valuable. Important to note is that Halifax county has only one publicly funded clinic and no federally qualified health centers to aid in female contraception usage.8 By the age of 18, a woman is more than 3 times as likely to have had a teen birth if they do not reliably use contraception.9 Because of these few resources, the importance of effectively connecting young women to these resources becomes paramount, and is a role that could potentially be filled by the proposed FCSA.

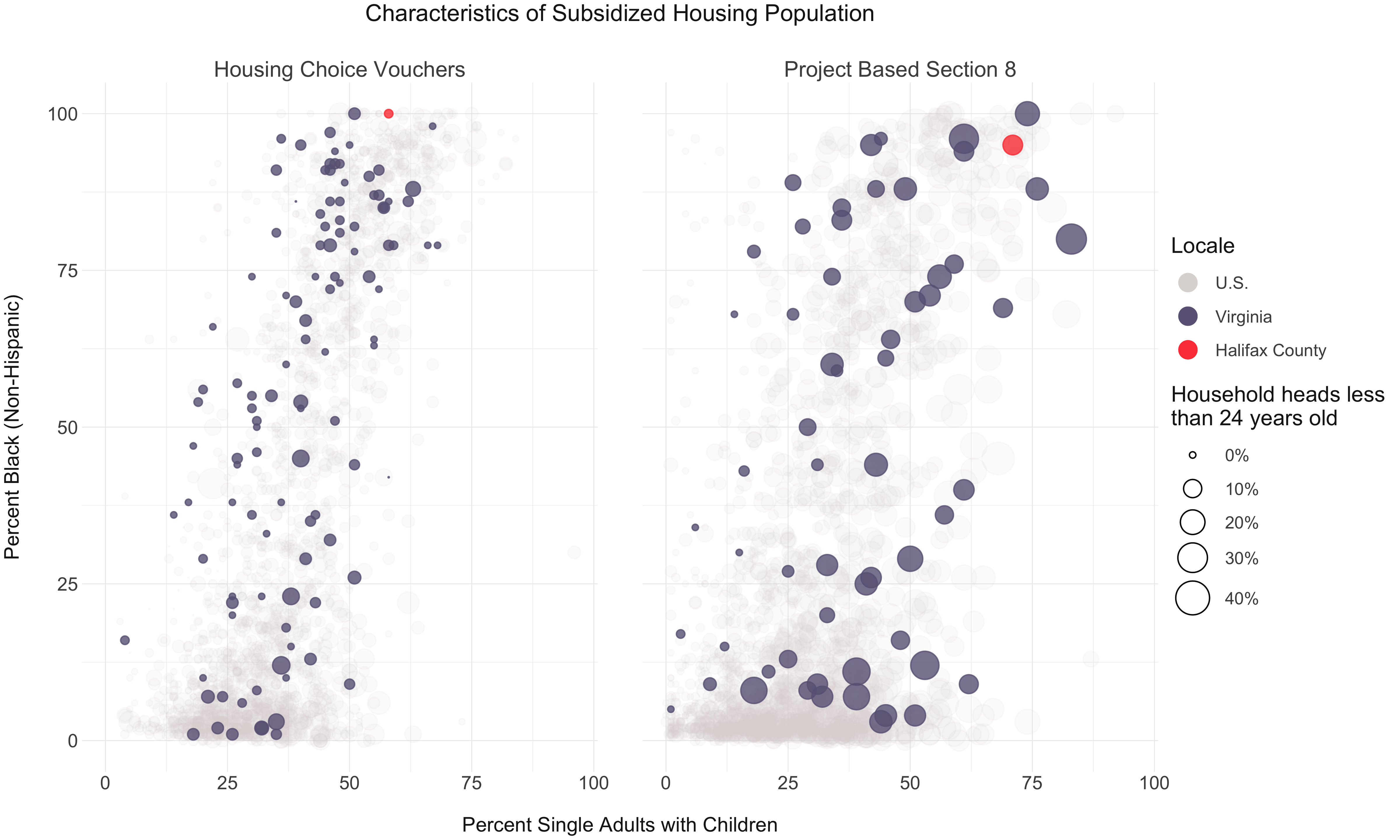

We can get a more granular look at these issues by exploring the demographic makeup of the subsidized housing population in Halifax. The population is almost exclusively non-Hispanic Black, and contains a disproportionate number of single adults with children. In addition, many of these family units are headed by someone (often the mother) younger than 24. The plot below highlights the difference in the ages of heads-of-households across the two common subsidized housing types in the county. Families headed by younger adults are more likely to live in project-based housing. While this does not indicate that project based housing is linked to incarceration, it does highlight a population that could benefit from community programs tailored to its particular needs, and emphasizes the relationships between the various social determinants we explore in this project. Teen births, housing opportunities, and racial discrepancies are all interrelated components in understanding incarceration and re-entry in Halifax County.

The impact of family structure on the health of children: Effects of divorce. (2020, November 2). National Institutes of Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4240051/↩︎

Teen Childbearing is Costly to Taxpayers. (2020). National Conference of State Legislatures. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/teen-childbearing-is-costly-to-taxpayers.aspx↩︎

About Teen Pregnancy | CDC. (n.d.). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 22, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/index.htm↩︎

Lynskey, D. P., Winfree Jr, L. T., Esbensen, F. A., & Clason, D. L. (2000). Linking gender, minority group status and family matters to self‐control theory: A multivariate analysis of key self‐control concepts in a youth‐gang context. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 51(3), 1-19.↩︎

Tasca, M., Rodriguez, N., & Zatz, M. S. (2011). Family and residential instability in the context of paternal and maternal incarceration. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(3), 231-247↩︎

National Center for Health Statistics. (n.d.). NCHS Data Visualization Gallery - Teen Birth Rates for Age Group 15-19 in the United States by County. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-visualization/county-teen-births/↩︎

Products - Data Briefs - Number 264 - November 2016. (2016, November). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db264.htm.↩︎

Guttmacher Data Center. (n.d.). Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://data.guttmacher.org/counties/↩︎

Products - Data Briefs - Number 209 - July 2015. (2015, July). Center for Disease and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db209.htm↩︎