Background

Putting the problem into context

Demographics

Given this project’s focus on health equity, we first wanted to develop a better understanding of the demographic makeup of Charlottesville and Albemarle. While this information is readily available from the American Community Survey (ACS), census tracts and block groups often don’t present an accurate representation of the population distribution in a town or city. We therefore used data from the ACS in Charlottesville to estimate the demographic makeup of the city’s actual neighborhoods. We used iterated proportional fitting to sample from the ACS data and re-aggregate values to the neighborhood level in Charlottesville. Of course, since Albemarle County does not have distinct neighborhoods, we use data reported for the census tracts in the county.

At the neighborhood level, neighborhoods south of downtown appear to have the largest proportion of black residents. There is a slightly larger Asian population in the Jefferson Park Avenue area south of the University of Virginia, but in general we will limit our observations primarily to black and white residents because of the relatively low representation of other groups in the area.

Data from the census also reveals the populations of rural areas of Albemarle County tend to be older than neighborhoods in Charlottesville proper and areas concentrated along the Route 29 corridor north of the city. Within the city, there are distinct pockets of young college students around the University of Virginia, but it doesn’t appear that any neighborhoods stand out in terms of both race and age makeup simultaneously, which may have indicated a particularly vulnerable area to focus on in our analyses.

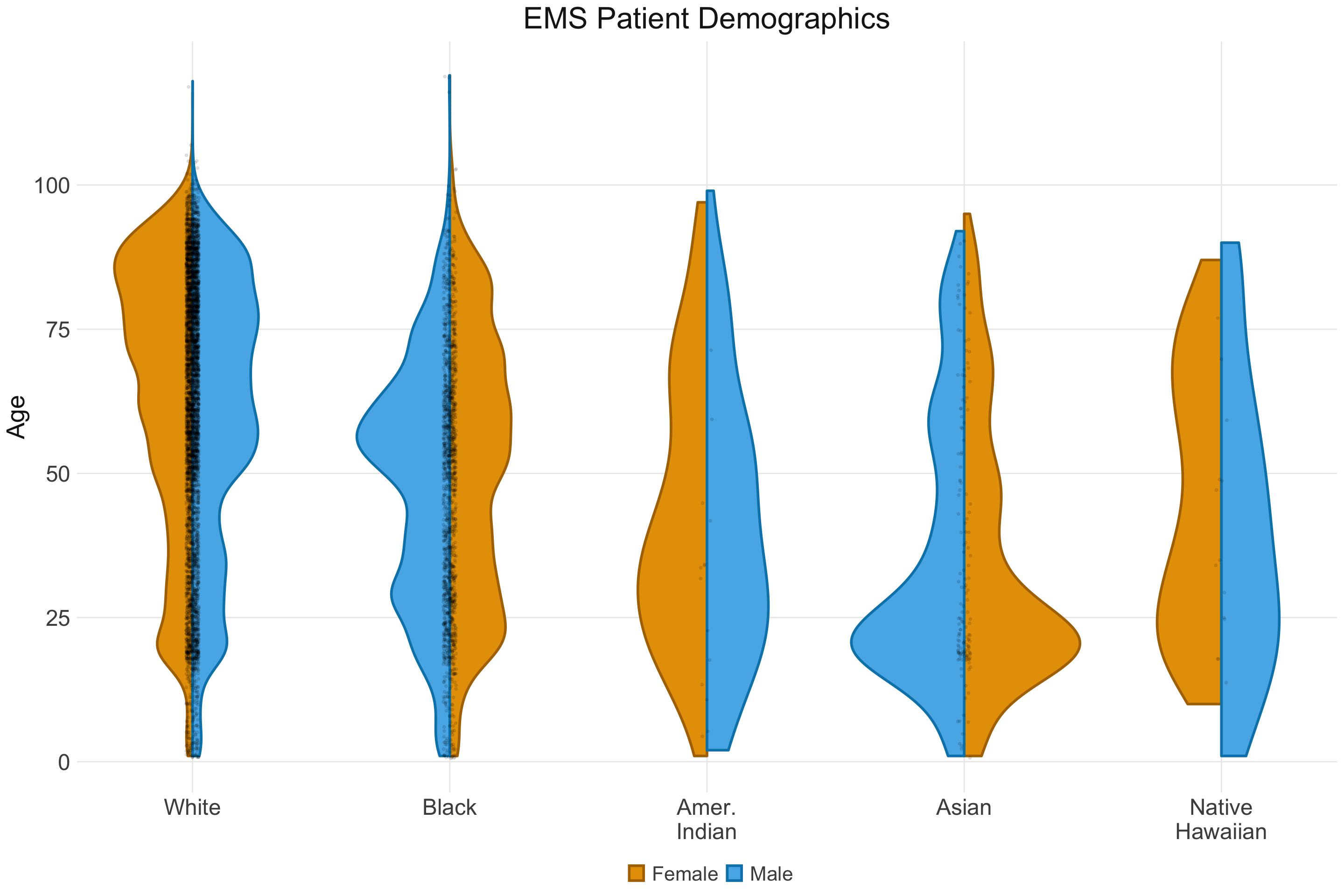

While these patterns describe the demographic makeup of the general population, it wasn’t clear whether these patterns would generalize to the population represented in the EMS dataset. Unsurprisingly, black and white patients make up the vast majority of the EMS calls reported between late 2016 and mid 2020, but differences in age distribution across racial categories are present. The large proportion of young adults amongst the Asian population may be a result of the presence of the university, which has a higher representation of Asians amongst its student population than do the city and county as a whole. Similar patterns may be at play in the slight bump at young ages for black patients as well. While this pattern is less noticeable for whites, this is likely a result of a generally larger white population muting out the effects of the university demographics. Given the increased risks of COVID-19 for older adults, the higher representation of blacks and whites at older ages is worth noting when considering groups at highest risk in Charlottesville.

EMS During COVID-19

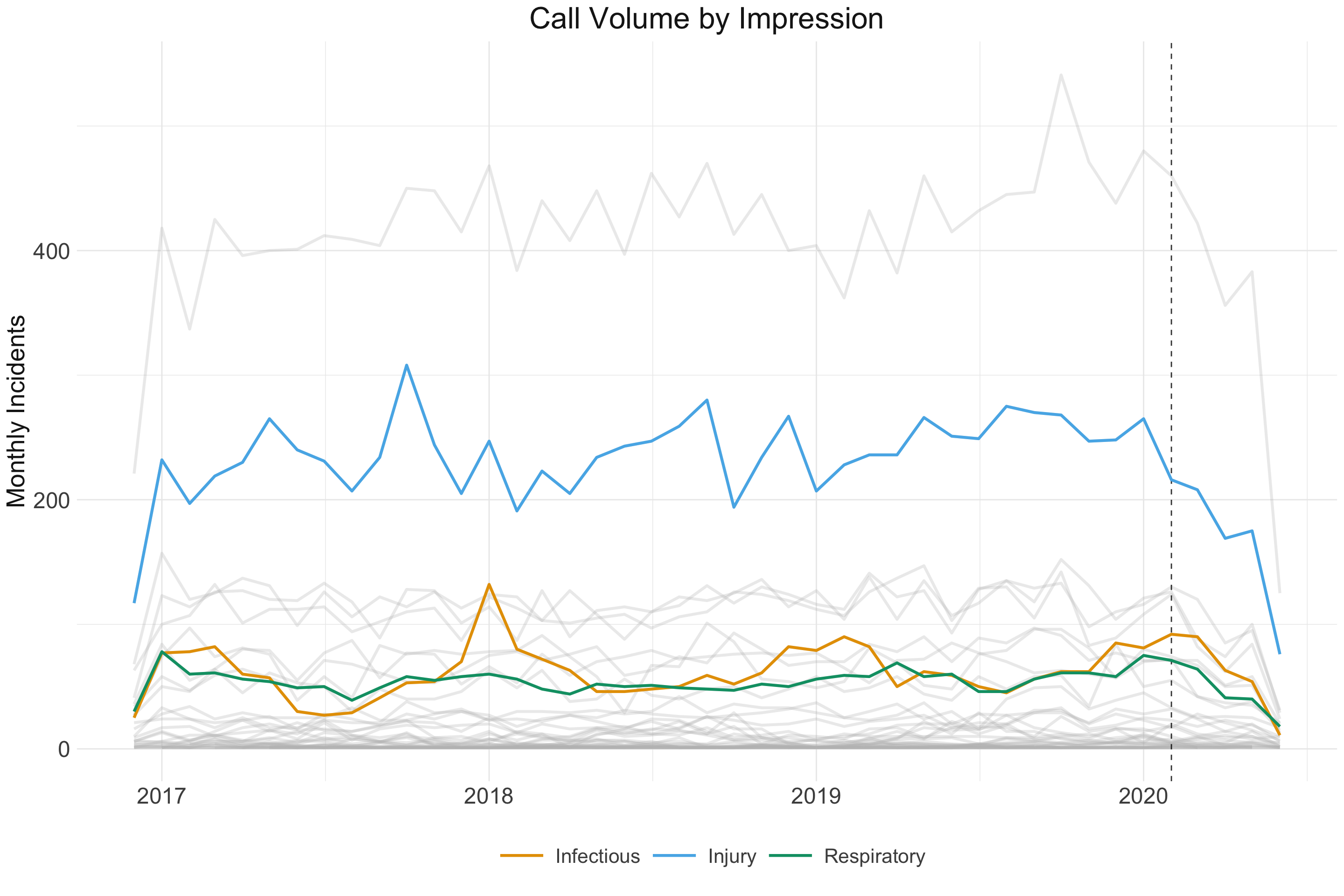

The pattern most immediately visible in the EMS data is the sudden drop in call volume after the onset of the pandemic. While slightly counterintuitive in the context of a rapidly-spreading virus, residents evidently have become much more hesitant to rely on EMS services in the past few months. This is likely a result both of residents’ fears about increased risk of contracting COVID-19 in hospitals and through contact with medical professionals (who may have been in contact with other COVID-19 patients) as well as a reduction in certain types of incidents resulting from stay-at-home orders. As a prime example, calls for injuries (many of which are related to traffic accidents) appear to have dropped at a faster rate than calls that may be related to COVID-19. However, there appears to be a reduction in call volume across nearly all call categories, suggesting that resident fears are likely the primary driver of this trend.

Call volume is not dropping uniformly across Charlottesville and Albemarle. The following map makes it clear that areas immediately surrounding the University have experienced the most drastic drop in call volume, which is almost certainly related to the departure of students from campus after the beginning of the pandemic (unsurprisingly, this is accompanied by a noticeable drop in alcohol-related incidents). Similarly, areas surrounding downtown have also seen a more noticeable decrease, likely related to the fewer interactions taking place in these public spaces after many bars and restaurants closed in the early stages of the pandemic.

Vital Statistics

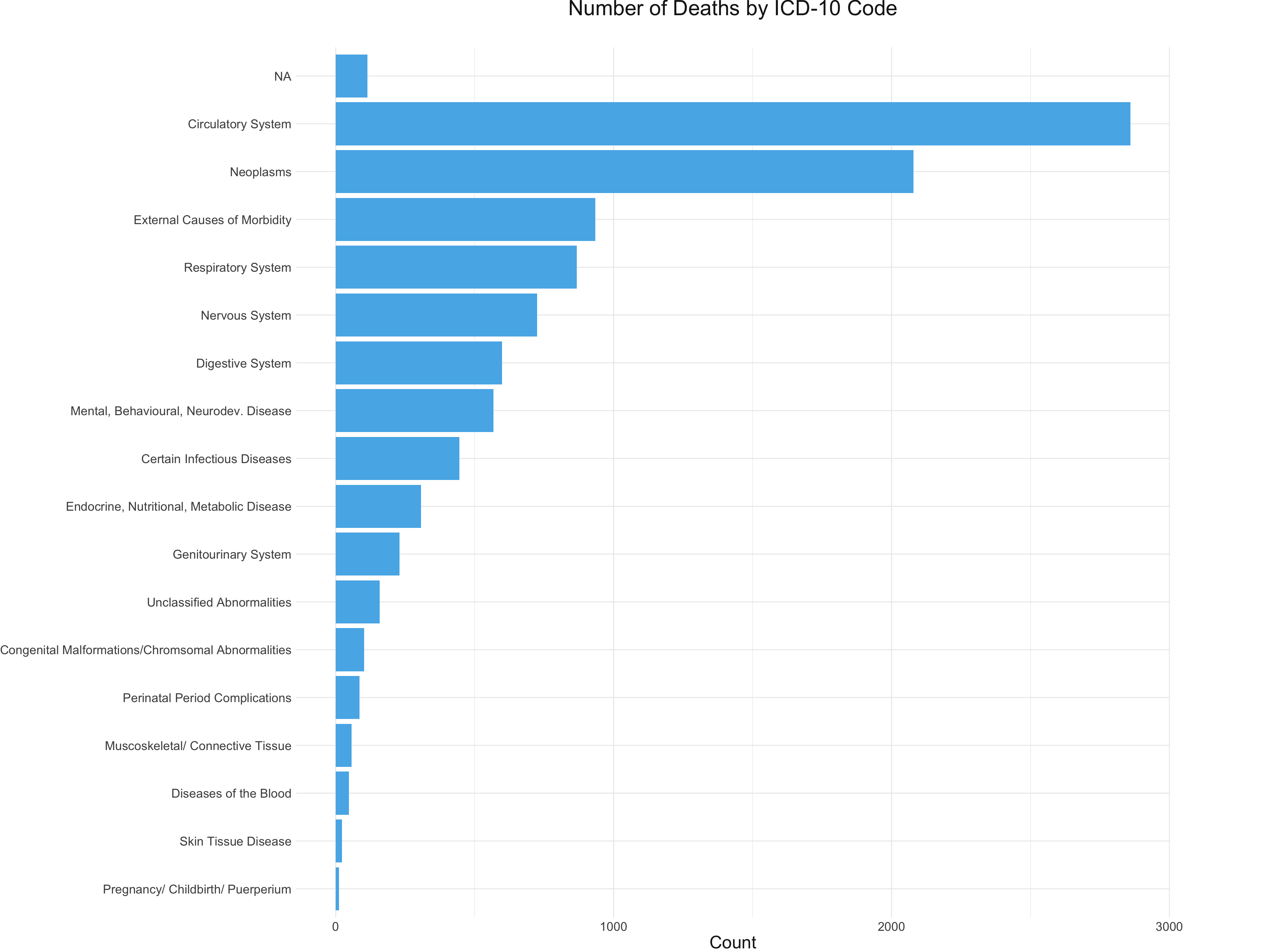

Using data from the Virginia Department of Health, we were able to investigate the trends in mortality in Charlottesville and Albemarle over the same period present in the EMS dataset. Notably, circulatory diseases and neoplasms make up an outsize proportion of all deaths. The high incidence of circulatory-related deaths is concerning given research suggesting that COVID-19 may disproportionately impact those with cardiovascular problems1.

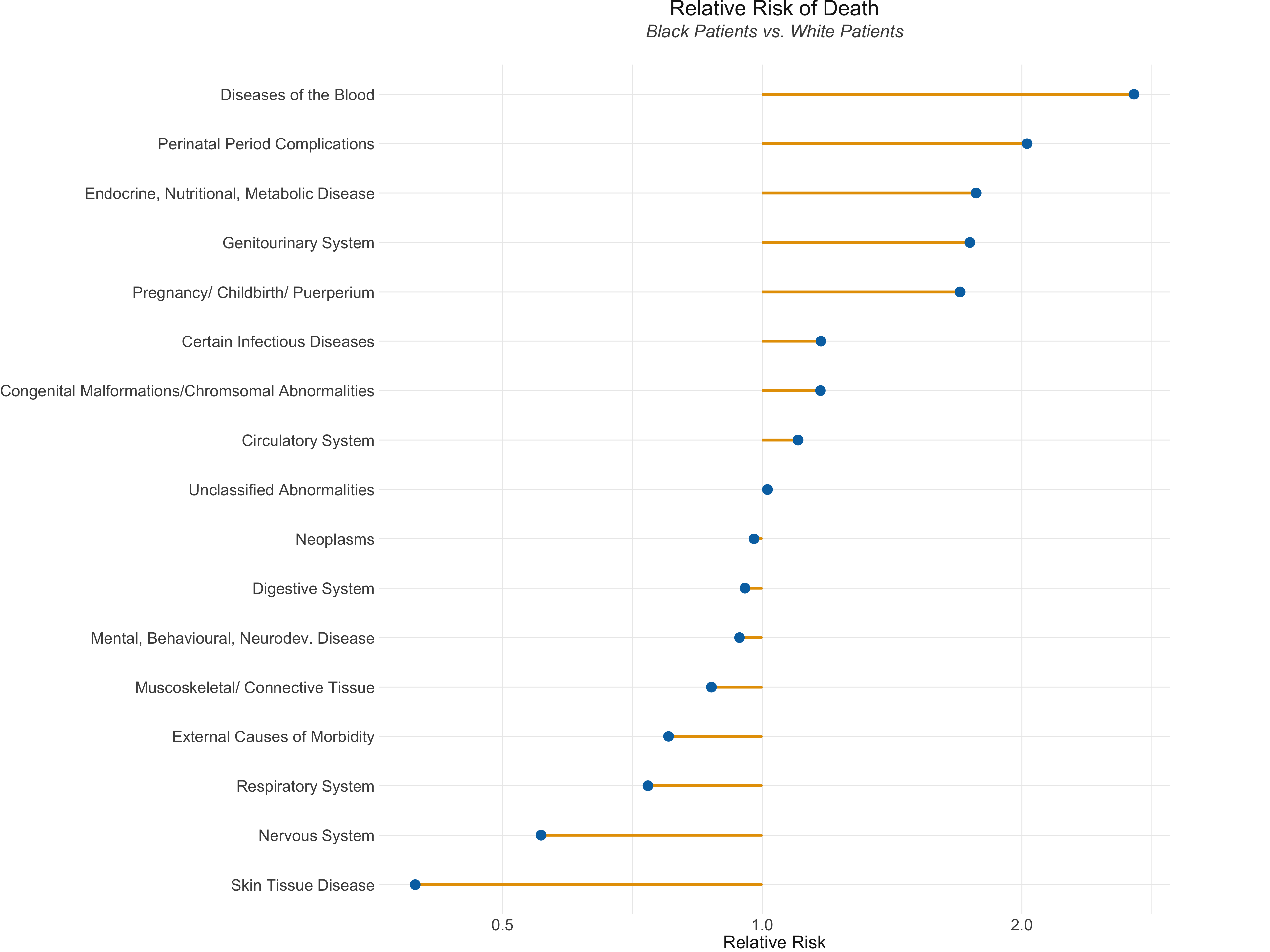

The VDH data also indicate that black patients are more than 2.5 times as likely to die from diseases of the blood and twice as likely to die from complications arising during the perinatal period. This is consistent with the widely-reported health disparities between black and white women when it comes to maternal morbidity.2 White individuals, in contrast, are more likely to die from skin conditions and, notably, respiratory illnesses. The circulatory disorders mentioned earlier appear to affect blacks and whites at roughly the same rate.

However, it is worth noting that these represent very general categories of death. As a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between underlying health conditions and COVID-19 develops, it may be valuable to explore these mortality trends with more granularity.

While the VDH data provided important context for understanding the health disparities in the region, we did not notice an overall increase in mortality since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting that more time may have to pass before we are able to assess its overall effects on mortality in the region. Additionally, the VDH data lacked information on patient race for many of the deaths that have occurred since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, making it difficult for us to explore the interaction between death counts, race, and the onset of COVID-19.

The patterns in general health outlined above provide important context as we interpret the results of our analysis of response times and exploration of COVID-19 symptoms across the region.

Mehra, M. R., Desai, S. S., Kuy, S., Henry, T. D., & Patel, A. N. (2020). Cardiovascular disease, drug therapy, and mortality in COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine.↩︎

Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:762–765. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3↩︎